When did humans first begin to compound wealth? No one knows for sure but some of the old forms of money date back to Mesopotamia during the second millennium BC; a clay tablet inscribed Amil-mirra will pay 330 measures of barley to the bearer of the tablet at the harvest time. According to economic historian Niall Ferguson, money is the root of progress, and the ascent of money has been essential to the ascent of man. Money is a medium of exchange which has the advantage of eliminating inefficiencies of barter; a unit of account, which facilitates valuation and calculation; and a store of value, which allows economic transactions to be conducted over long periods as well as geographical distances.

With the creation of money came the creation of credit. The word credit originates from the Latin verb credere which means to believe or to trust. In economic terms, credit represents the trust extended to a borrower with the expectation that it will be repaid in the future. In many cases, what is an asset to you is a liability to someone else – the twenty-dollar bill in your pocket is an asset to you, but it is a liability for Uncle Sam. Money is not metal, or paper, or plastic; it is trust inscribed.

Interest is an extremely complex subject. The Hebrew word for interest, nescheck, derives etymologically from the bite of a serpent. To French anarchist Joseph Proudhon, interest constitutes a reward for idleness, the basic cause for inequality and poverty; he called it theft. To Benjamin Franklin, time is precious; time is money. Time is the stuff of which life is made. Interest is therefore natural, just and legitimate.

To Albert Einstein, if you understand compound interest, you earn it; if you do not, you pay it. But what is compound interest? Compound interest is the interest calculated on the initial principal which also includes all the accumulated interest from previous periods. In simple terms, it is interest on interest which over time allows the principal to grow exponentially.

"Compound interest is the interest calculated on the initial principal which also includes all the accumulated interest from previous periods. In simple terms, it is interest on interest which over time allows the principal to grow exponentially"

Commercial arithmetic came from the Phoenicians, the great merchants of the early Mediterranean, but we owe a great deal to the Italian merchant bankers of the fourteenth century who financed the Renaissance. At a time when only nobility and the clergy were highly educated, it is not surprising that a Franciscan Friar named Luca Pacioli, the “father of accounting” published Particularis de cumputis et scripturis and his greatest work Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportione et proportionalita. Pacioli taught mathematics to Leonardo Da Vinci, and remarkably five hundred years after his bookkeeping treatise was published, it remains the foundation of modern accounting and the capitalist system.

Pacioli’s work provided the foundation for the Rule of 72, a simple way to estimate how long it will take to double your money given a fixed annual rate of return. The formula is 72/r, where r is the annual interest in percentage terms. For example, at an interest rate of 8%, an investment will double in approximately 72/8 = 9 years.

The doubling of capital is easy to understand in its initial stages, but it is mind bending as the numbers get bigger. Let us examine the case of two of America’s early settlers. Edward Hopkins was born in 1600 in Shrewsbury, England and sailed to Boston in 1637. John Harvard sailed in the same ship but died in 1638 and left a bequest that gave the college his name. When Hopkins died in 1657, he left his New England property in a charitable trust “for the breeding up of Hopeful youth in the way of learning both at ye Grammar School and College for the public service of the country in future times”. In 1715, Harvard received £771, which if invested at 9% with 5% spending would have become $164 million in 2023 dollars. Without spending, they would have become $314 trillion!

Here is another example of the power of compounding. If you take a standard sheet of paper that is 0.1mm thick, after the first fold it is 0.2mm thick, after the second it is 0.4mm, and so on. After only 42 folds, you can get to the Moon or 384,400 km. If you fold it 43 times, you can get to the Moon and back.

| WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS IN MODERN FINANCE?

Avoid consumer debt at 20%

Warren Buffett hates credit card debt, and it is unlikely that you will find an investment with a higher rate of return. Brunello Cuccinelli, the Italian creative director and CEO of his eponymous brand, is skeptical of leverage because he learned at an early age from his father that in Italy the only thing that works on Sunday is money.

Start saving a soon as possible

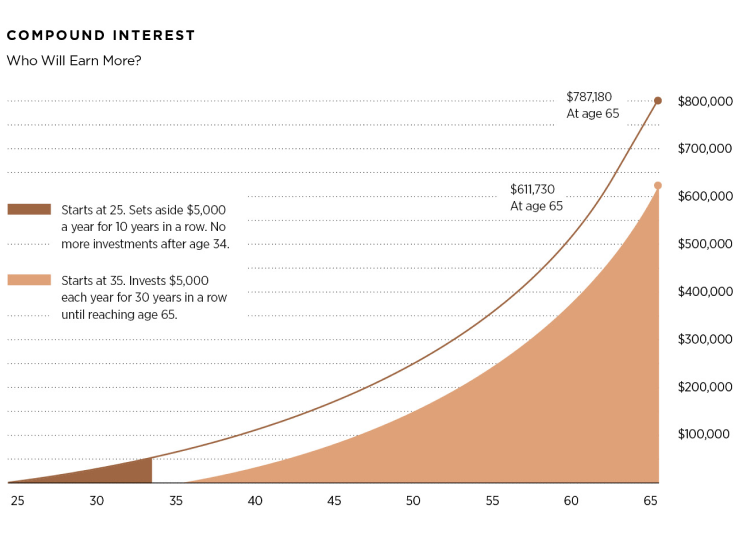

If Sheila sets aside $5,000 a year for 10 years in a row starting at age 25 and makes no additional contributions after age 34, at an 8% interest rate compounded annually, she will have $787,180 at age 65. If Jack starts the same process at age 35 and contributes $5,000 each year until reaching 65, he will only have $611,730. This example shows how Sheila takes advantage of compound interest allowing more time for the money to grow.

Be as frugal as possible in your personal life

Particularly in the earlier years. This is exemplified by the Hopkins donation to Harvard. The difference between a 5% spend rate and no spend rate is a factor of almost 2 million to 1.

Be tax sensitive

We have a silent partner called Uncle Sam; take the time to understand the rules and be tax efficient. For example, if you have a good business with good growth prospects and one investor needs income, it makes no sense to distribute a dividend with tax consequences to all taxpaying shareholders. For those who need income, it is better to create a synthetic dividend by selling a portion of their shares. This is particularly true if the business sells at a premium to book value.

Be cost sensitive

Some hedge fund fees are too high, particularly when adjusting for tax inefficiency and the asymmetric distribution of gains and losses.

Think long-term

Thanks to the growth, productivity and innovation of our corporations investing in equities for the long term has been a winner’s game. That is only true if you think in decades; if you need to know the value of your account on a given date, the stock market is not the place for you.

Volatility is risk

According to Charlie Munger, the first rule of compounding: “Never interrupt it unnecessarily.” Many investors do not stomach volatility well, and if you have a portfolio that is not right for you, you run the risk of selling at the wrong time.

Choose your partners well

You cannot do a good deal with a bad person. A bad partner can hurt your performance and your mental health.

Beware of bubbles

Take Benjamin Graham’s advice on the matter “Our old ally, experience, tells us it is better to sell and pay the tax than not to sell and repent.”

Mind your alpha

Spend your energies in the asset classes with greater return dispersion; this was one of the reasons that David Swensen was so successful at Yale.

Be a learning machine

No matter how good you are, you can do things a little better.

Raúl Pineda

Managing Director, Morgan Stanley.

morganstanley.com

Morgan Stanley

Leading global financial services firm with offices in 41 countries and a workforce of over 75,000 employees.

morganstanley.com